Complex or just complicated?

31 May

Our thoughts can be either complex or complicated or both. One can speak in a really clear way or in a very complicated way. In either mode, one can be saying very simple things or very complex things. It is therefore important to distinguish between these two adjectives. This blog post is on speaking about complex things in simple terms and how we often get it wrong.

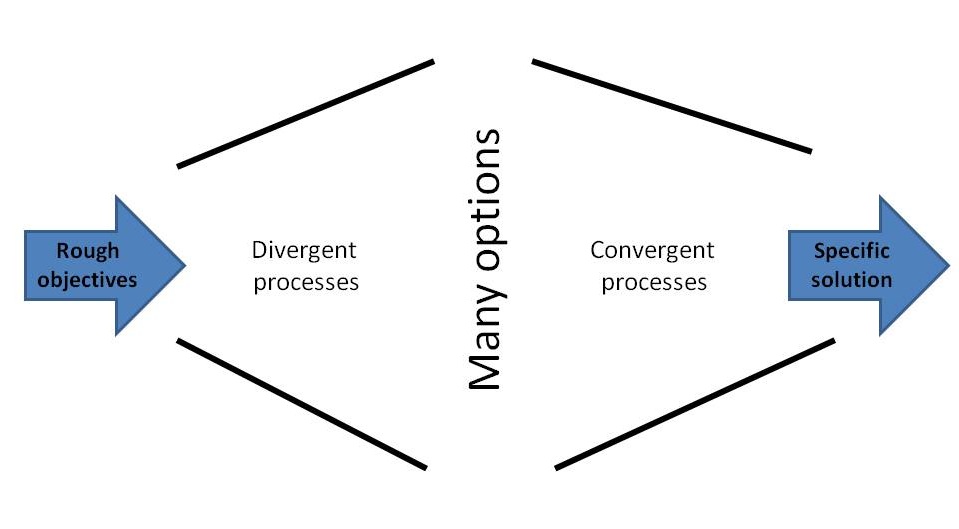

If we know only a little about some topic, we speak about it in simple terms if at all, using our everyday language. This is because we do not know what we do not know, so we by default have to keep it simple. It is worth noting however, that simplicity does not always equal to brevity for some people can take a really long time to convey a simple thought they do not even know much about.

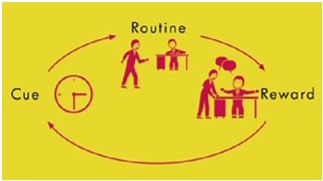

When we dig deeper into a topic and we learn more about it, we start understanding parts of it. But we also realize that there is so much more to learn about it – we know what we do not know. This is the most tricky phase. Because we are eager to use all our new knowledge, we are no longer able to speak in simple terms only. Additionally, by trying to acknowledge and compensate for the known unknowns, we start speaking in a really complicated way. Our message becomes a lot less comprehensible.

It is only when we become really familiar with the topic that we are able to speak about it with clarity again. We know what we do know. We are able to pick only aspects most relevant to our audience and convey a complex thought in simple terms. This is the ideal phase. I always enjoy coming up to somebody with deep knowledge of an unusual field and asking that person to tell me in couple sentences about what they do. If they really understand their stuff, they are usually able to do so.

It is important to be aware which phase we are in. If we are in the first one, we should be careful not to be making any big claims about our knowledge of the topic. We should acknowledge we do not know much about it, speak briefly about it, and ask questions or learn more about it. If we are in the second phase, imagine how lost the poor guy on the other side of the table must be. We are now in a position to synthesise and to ask better, more targeted questions about the topic so we should do that rather than start rambling for ages. Finally in the third phase, we can share with others our gift of understanding complex topics in beautiful simple terms. I think this makes much better impression than using complicated terms just to show off we know them.

And always remember what Albert Einstein said:

“If you can’t explain it to a six year old, you don’t understand it yourself.”

Recent Comments