My theory of happiness

22 Oct

Happiness is one of the most discussed things in the world but there seems to be very little consensus on what it is that actually makes a person happy. I have travelled around the world and spoke to many people from very diverse backgrounds and I have realised that things such as how rich or healthy or fat or colourful or intelligent or how much people we have around us do not seem to be very good determinants of how happy we are. Instead, I realised that happiness is about being in balance about what we think we could be and what we are. I decided to call it living in an ‘ignorance bubble’. In this blog post, I will firstly define what an ignorance bubble is, secondly elaborate on my conceptualisation of happiness and finally explore how people move between the states of being happy or not.

It is worth mentioning at the beginning that the word ignorance is not as negative as its connotations would normally suggest. It comes from Latin ignorantia which means ‘not knowing’. It is thus perfectly human to be ignorant because nobody can know everything. I would like to distinguish two relevant types of ignorance for the purpose of this blog post. It is firstly ignorance about how capable we are, a ‘capability’ ignorance, and secondly ignorance about what we can be doing/what we can have, a ‘can do/have’ ignorance.

An example of the first type of ignorance, the capability ignorance, is a guy who is a sailor because that’s how good he thinks he is. In reality he is capable enough to be a captain but he is perfectly happy about being a sailor because it never crossed his mind that he could be a captain. He lives in ignorance about his capabilities, in an ignorance bubble, and is happy in this bubble. Another example is a woman watching TV in a slum dwelling and seeing people living in beautiful houses in the movies. Despite the fact she might be as intelligent as people living in those houses, her circumstances made her think that she will never be able to afford such a house and therefore it does not really worry her she does not have one.

An example of the second type of ignorance, the can do/have ignorance, is a man eating plain food his whole life. He has never tasted for example a well prepared piece of meat and therefore he is not sad he cannot eat it every week. Another example would be an Indian girl living her whole life in a dusty, crowded city. She has never lived in countryside nearby a forest and has never breathed clean air. She lives in ignorance, an ignorance bubble, about what her environment can look like and therefore she is not sad about what it is.

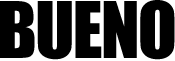

We can now define an ignorance bubble as the sum of our knowledge and beliefs about what is possible at any given time. We can also distinguish five different states where we can be relative to our ignorance bubble (see Figure 1). It is where we are that defines if we are happy or not. In state 1, our ignorance bubble, the black oval, is identical with what our life actually is, the red oval, and we are happy (more detailed examples of what happens in each state follow). In state 2, our bubble bursts or put another way, it expands – we now believe our life can be better than what it is and we are unhappy. From state 2, we can move either to state 3, which is to do nothing about it and stay unhappy, or to state 4, which is to actively attempt to improve our situation to match it to what we now believe is possible; this effort makes us initially happy. We can again move in two directions from state 4. We either succeed in our efforts and our situation improves to a point it matches our new, expanded ignorance bubble which moves us to the happy state 1 where all is in balance. Or we do not succeed and despite our efforts our situation does not match what we believe is possible. At that point we have to make a decision; we either move to stage 3 where our ignorance bubble is permanently bigger (better) that what our situation actually is and we are unhappy or we realise that the idea that burst our initial ignorance bubble is actually not possible at the moment (we give up on that ambition), we readjust our ignorance bubble back to its original form, move to the balanced state 1 and are happy again.

Figure 1: 5 states of happiness relative to our ignorance bubble

State 1 –living happily in an ignorance bubble

One way I believe people can be happy is by living within their ignorance bubble having achieved what their capability and can do/have ignorance tells them they can achieve. I know many such people and I respect them very much because they have worked very hard to make things be as good as they believe they can be and consequently they are happy now. I, for example, stayed once for a weekend with a poor Colombian farmer living high in the mountains. He told me that his biggest dream is to see an ocean. This was quite doable since he would have to take a chiva, the local bus, for two hours to the nearest town and from there it would take him about ten hours on another bus to get to the ocean. He would be able to afford the trip if he saved for some time. But he did not believe it is possible for him to go there – nobody like him he knows in his village has ever seen the ocean either. The fact he has not seen the ocean yet and probably never will does not however make him unhappy in the slightest; he lives happily in his ignorance bubble.

State 2 – painful puncturing of our ignorance bubble

Every now and then somebody or something comes with an idea and punctures our ignorance bubble. If our can do/have ignorance is punctured as we for example taste a good steak and we like it (we have realised how plain our food is in comparison to the steak) our capability ignorance can still save us. If we will still think that we are simply not able to earn enough money to keep buying that steak we will happily get back to our plain dishes. A problem arises when we also start believing that we are capable enough to secure that steak meat yet we do not have it at the moment (see note 1). We become unhappy at that moment because our ignorance bubble got punctured – it expanded and no longer matches the reality of our current lives. At this moment, we have two options. Those are firstly to do nothing and secondly to actively try to make things as good for us as we believe they can be.

State 3 – doing nothing and being unhappy

The easiest option (in the short term) is always to do nothing. I often see people who somehow got their ignorance bubbles punctured and believe their lives can (they would say should) be better but do not attempt to improve them in any way. Instead, they resort to complaining and relying on others to help them. This inaction combined with belief that their lives should be better than they are now makes them unhappy.

State 4 – happily trying to improve our situation

A much better alternative is to act upon the capabilities we have realised we have and to improve our lives to the point where we now think we should be given our newly expanded ignorance bubble. I believe that once people embark on this ‘equilibrating’ journey their happiness level suddenly increases. They feel good because they are doing something about their situation. They might not be eating the steak yet, but they feel they are at least working on getting there which is initially almost as good as having it. If all works out well and we get to where we want to be, that reality becomes our new ignorance bubble, we are now in balance with it and therefore move to the happy state 1. If things however do not work out as envisioned despite our best efforts, we get to unhappy state 5 where our improvement efforts keep ending in vain.

State 5 – being unhappy from not getting the results

We all have sometimes tried hard to achieve something but we just could not get there. In this state we still believe our situation should be better and we are actively trying to do something about it; to little effect however. This makes us unhappy. We can always try to get there in a different way but should that not work out as well, two things can happen. We can either cease our efforts to improve our situation but still keep believing that it should be better. This would move us to the unhappy state 3. Alternatively, we can accept that we are realistically not capable at this moment to get there or that it is not worth the effort and readjust our expectations accordingly. This means to contract our ignorance bubble to our initial size and live happily as we did before in our original state 1.

I believe it is very important to try hard to improve our situation whenever our ignorance bubble gets punctured. It is only through exerting our own effort that failing to get where we want to get, we are genuinely able to readjust our expectations, our ignorance bubble, back to its original balanced state. Only then we can stop being worried about not having something (see my previous blog post on never regretting ). Equally importantly, if often happens that once we get where we thought we wanted to get, we realise it is by far not as good as we imagined it to be. We can then give up on that need and get happily back to our original ignorance bubble. At the same time, I believe the only way out of state 3 is to try, to get to state 4, for the same reasons I have just mentioned.

What I have tried to demonstrate here is firstly that how happy we are is not contingent on how much we have in absolute terms but rather on how much we have relative to what we believe we are capable of having and relative to how much we believe we should have. This relates equally to physical objects, money, people around us or feelings. Secondly, I wanted to show that how happy we are is dependent on the actions we choose – which state we decide to be in. The only state we cannot fully control is state 2 – when our ignorance bubble is punctured. It often just happens. Someone tells us a new thing, we read something impactful or we experience something new. Alternatively, we can also consciously decide to puncture and expand our own ignorance bubble and set ourselves new goals. But I believe we are in full control of moving between all the other states as shown in Figure 1 and described above.

This means that while we cannot directly control how happy we are by simply telling ourselves now I will be happy, we can influence it by consciously deciding which actions we take. Next time your ignorance bubble is punctured therefore, think carefully how you are going to react so that you move through state 4 back to balanced state 1 and do not get stuck in the unhappy passive state 3. In a similar fashion, if somebody around you is not happy, you can use this diagram to figure out in which state the person is, why they are there and help them by guiding them to a more happy state accordingly.

Note 1: Using steak meat as a proxy for happiness might seem rather superficial but it is not for two reasons. Firstly, it is only a metaphor; you can substitute the steak for a loving, intelligent, funny and attractive girlfriend, a different nationality, being healthy or whatever you desire. Secondly, meat is one of the first things people spend their money on upon escaping absolute poverty and its consumption is an important indicator of ones poverty level.

Recent Comments